Hold My Pipes. (Diving into the Wonders of Nu Shell for the First Time)

It’s been a while since I delved into the mesmerizing intricacies of shell scripting. Nah, shell scripting still sucks. Or does it have to be?

POSIX Taste™

My first shell, like other people, was bash.

And so, I grew with program 2> /dev/null, \[\[ \"\$x\" -lt \"\$y\" ]], echo \"\$\(<filename)\", program | tee out, and other weird shell syntaxes. They’re fine if you’re just using them interactively, but programming with those? Sounds hellish. Yet I somehow liked it, it was the first language that I truly used (..I guess, because I had to rice my Linux desktop).

The POSIX sh shell syntax is made to be readable and easy to write for day-to-day tasks. For example, if you want to process some input string, you can just call the command directly and any arguments following it, right? programname file1 file2. Much better than programname(file1, file2). Wanna then process the output again? Pipe it to another program.

The problem comes when you try to do some more complicated tasks, or even code with the language. This is also made a lot harder as neither sh nor BASH comes with many useful built-in commands. Luckily, you can rely on core utilities for that, like cat, sed, tee, tr, uniq, etc. UNIX is made so that components work on their own independently, yet still confine to some standard that allows them to work together: everything, and by this I mean EVERYTHING, is string! While this is a brilliant idea, we now get a tremendous issue.

As we know, there is no distinction between variable=2 and variable="2". There is also no distinction between [ "abc" == "def" ] and [ abc == def ]. Works fine for most automation tasks, but really, we all know that type-strict languages are 10 times better than their counterpart dynamic languages. Imagine the amount of mistakes you can make with this! You won’t even get super meaningful error messages if you called your command with the wrong arguments.

Speaking of argument-processing, to take arguments in a function you just use the special variable $1 (1st argument), $2 (2nd argument), and so on. $@ expands to the whole arguments and quotes them, while $* expands to the whole arguments without quotation marks.

saysomething()

{

echo "$@"

}

And you call it like this:

$> saysomething "hi" "there" hehe 123

hi there hehe 123

WEIIIIRDDD YEAH. It’s like everything is black magic (until I read the manual page). But I did not know programming, so this was my very first taste of programming.

But of course, we know it gets worse. How do you get, say, a list of all files of a directory?

I’d do it like this:

files="$(ls --quoting-style shell)"

Yup what is this now?! Well yeah, ls --quoting-style shell lists a directory and returns the whole listing with each file surrounded with quotation marks. But this is simply a hack because we know that the shell separates items by white spaces. Which means that declaring a variable like files=(hello world) means you’ll get an array with length of two with items hello and world. To prevent splitting, we have to quote the hello world together like files=("hello world").

We hate hacking, don’t we?

Nu: Battery Included

Up until recently, I thought that shell scripting would always be so daunting and annoying. That is, until I took a real look at Nu Shell.

Nu shell is a shell written in.. Rust! I would say that it’s a shell for (Rust lover) hipsters, haha (more on that later)

By the way, how do you get a list of files in Nu?

$> ls

╭───┬───────────┬──────┬────────┬─────────────╮

│ # │ name │ type │ size │ modified │

├───┼───────────┼──────┼────────┼─────────────┤

│ 0 │ Desktop │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 3 weeks ago │

│ 1 │ Documents │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 2 weeks ago │

│ 2 │ Downloads │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 5 days ago │

│ 3 │ Music │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 4 weeks ago │

│ 4 │ Pictures │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ a day ago │

│ 5 │ Templates │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 4 weeks ago │

│ 6 │ Videos │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 3 days ago │

╰───┴───────────┴──────┴────────┴─────────────╯

WUHH, TABLES! But it’s not just merely printing a table—it’s a ready-to-manipulate table. We’ll see how.

Variables Made Easily Strict

I’ve tried Nu shell around a year or two ago, and from what I recall I seem to not be so excited about it. Nu has a quite Rust-like syntax. So, perhaps it’s because I have not dipped my toes into Rust yet by that time.

The first awesome thing I noticed from Nu is how everything has types. Yup, this is not like those Python type annotations. It’s actually really strict here.

Let’s say that I do:

$> let variable: float = 1

Nu will complain (in a really clear way):

Error: nu::parser::type_mismatch

× Type mismatch.

╭─[entry #3:1:16]

1 │ let b: float = 1

· ┬

· ╰── expected float, found int

╰────

Now that’s cool. But of course, you can declare variables and let Nu infer the type automatically too. Phew.

$> let x = 100

# Works fine!

How do we access the variable? Well thankfully, you still use the good old dollar sign syntax like so:

$> print $x

100

Also, it’s perfectly an int, as said by describe:

$> $x | describe

int

Now, normally in POSIX sh, you can’t really do anything just by entering an expression like $x because the shell will evaluate the variable and treat it like a command (if I set c=echo and then I type $c hello, you will basically run echo hello. Weird)

In Nu, that’s not a thing. Everything in Nu is a straightforward expression—even commands (the output would be the evaluation result, which can then be piped into another command or be stored in a variable). In fact, there is no dynamic runtime code evaluation. There is no eval command or something similar.

In Nushell, there are exactly two steps:

- Parse the entire source code

- Evaluate the entire source code This is the complete Parse/Eval sequence.

Greeeaat! So this will reduce a significant amount of software bugs. And that’s how I’m able to directly manipulate the $x I typed. The $x gets evaluated simply to whatever the value of it is and because there is a pipe at the back, it will be set as the input for the describe command. I can literally turn Nu into a pocket calculator! Well, almost, because while 2 * 2 indeed evaluates to 4, 2*2 is still treated as a command. But not bad, compared to POSIX shell where you have to use the expr command like so: expr 2 * 2.

String Interpolation

How do we print out our variables with other strings?

String interpolation in Nu is kinda like in POSIX sh, except that you start your string with a dollar sign:

$> let x = 100

$> print $"This will get evaluated: ($x), also works with commands: (whoami)"

This will get evaluated: 100, also works with commands: cikitta

And for anything you need to evaluate you use the parenthesis, as usual.

Strict.. but Flexible

What happens when you make a list like this?

$> let array = ["item one", 100, (ls)]

I originally thought that this would fail—but nah, this is perfectly fine. The type of the array would just be list<any>. It does seem like a big performance trade-off, but that’s fair considering that this is a shell language. A completely static typed shell would sound like hell.

Immutability

Ah, and of course, all variables are immutable by default.

To declare a mutable variable, use the mut keyword:

$> mut x = 100

$> $x += 10

$> $x

110

Also, yep, reassignment somehow requires you to use the $x syntax which in my head kinds sounds like evaluating $x first and assigning 10 to it which doesn’t quite make sense, but I guess that this is to prevent confusion with shell commands.

Pipelines!

Nu still has pipes like POSIX sh. I’m sooo glad pipes still exist as it is ^w^ In fact, pipelines is the main paradigm of Nu shell.

Nu handles the input/output of commands based on whether it is a builtin command or not. When it is a builtin command, Nu will be able to adapt the behavior such that data are structured and typed.

Table Manipulation

Going back to the directory listing from before. We can manipulate the table! Let’s say that we only need the file names. We can use the get command to retrieve a single column:

$> ls | get name

╭───┬───────────╮

│ 0 │ Desktop │

│ 1 │ Documents │

│ 2 │ Downloads │

│ 3 │ Music │

│ 4 │ Pictures │

│ 5 │ Templates │

│ 6 │ Videos │

╰───┴───────────╯

Without the headers, we now know this is an array. Or precisely, a list of string.

Now, of course, we can store this into a variable for use.

$> let files = ls | get name

We can then access the file names again:

$> $files.0

Desktop

$> $files.1

Documents

…using a Rust tuple-like syntax. I really wish that \[idx] is a thing, because otherwise, dynamic list accesses would be so painful (we’re talking something like \$arr | get \$idx here).

Even More Practical Pipelines

For example, you can convert something with a type of duration into a string:

$> 10min | into string

10min

And you can see that it is indeed a string:

$> 10min | into string | describe

string

If I did not convert the input it would’ve been just a duration.

$> 10min | describe

duration

Perfect! Quite neat. The great thing is that external/non-builtin commands can also be piped, though everything would then be just string/binary.

The weird result of this pipeline-oriented processing is that you can end up with something cursed like this:

while ($number | math ln | math floor) < 10 {

print "do something"

...

}

Notice the funny \$number | math ln | math floor? Yeah that looks super weird. But it’s great for what it is—a shell. Plus, say goodbye to parentheses (like floor\(ln\(number))) :D

The use of parentheses to surround the expression \$number | into int | math floor is needed because we need to evaluate those first. Kinda like the equivalence of \$\() in POSIX sh.

Pipelines Abuse

You can abuse pipelines with the $in variable.

Let’s say we want to manipulate some string first and pass it as an argument to a command. A normal person would totally do something like:

$> open ("~/Document/text.txt" | path expand)

...

The inner command will get evaluated first, then the open.

However, for weird code lovers, this is also valid:

$> "~/Document/text.txt" | path expand | open $in

...

..as $in will be set to the input from a pipeline when it exists. That’s such an abuse, no? :P

Who Loves Closures?!!

I sure am a big fan of closures, especially Rust closures :)

And great news, Nu has a Rust-like closure. A bit different syntax, but the idea is still the same.

Let’s say we have a directory listing again:

$> ls

╭───┬───────────┬──────┬────────┬─────────────╮

│ # │ name │ type │ size │ modified │

├───┼───────────┼──────┼────────┼─────────────┤

│ 0 │ Desktop │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 3 weeks ago │

│ 1 │ Documents │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 2 weeks ago │

│ 2 │ Downloads │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 5 days ago │

│ 3 │ Music │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 4 weeks ago │

│ 4 │ Pictures │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ a day ago │

│ 5 │ Templates │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 4 weeks ago │

│ 6 │ Videos │ dir │ 4.1 KB │ 3 days ago │

╰───┴───────────┴──────┴────────┴─────────────╯

Let’s do something to each one of them! Forget the pain of xargs LOL.

$> ls | each {|item| $"($item.name) is here"}

╭───┬───────────────────╮

│ 0 │ Cloud is here │

│ 1 │ Desktop is here │

│ 2 │ Documents is here │

│ 3 │ Downloads is here │

│ 4 │ Music is here │

│ 5 │ Pictures is here │

│ 6 │ Templates is here │

│ 7 │ Videos is here │

│ 8 │ src is here │

╰───┴───────────────────╯

We have just mapped the input table into a list of strings, similar to Rust’s map method on vectors! How beautiful.

Shell Scripting is Now Fun!

Here’s the most exciting part. Nu takes away the most daunting task of shell scripting: arguments processing.

The ordinary way to process arguments when you write a POSIX shell script would be to use getopts. But that’s extremely annoying:

while getopts hnSzHRZ opt; do

case "$opt" in

n) ZZZ_MODE=noop;;

S) ZZZ_MODE=standby;;

z) ZZZ_MODE=suspend;;

Z) ZZZ_MODE=hibernate;;

R) ZZZ_MODE=hibernate; ZZZ_HIBERNATE_MODE=reboot;;

H) ZZZ_MODE=hibernate; ZZZ_HIBERNATE_MODE=suspend;;

[h?]) fail "$USAGE";;

esac

done

shift $((OPTIND-1))

Another way would be to eat the arguments one-by-one, i.e by acting upon the first found argument $1 then shifting the arguments index.

With Nu shell, any function you define are treated as commands. Nu will then automatically generate command completion and a help page like so:

$> def greet [name: string, --loud] {

> if $loud {

> print $"HELLO, ($name | str upcase)"

> } else {

> print $"Hello, ($name)!"

> }

> }

Now we get a nice help page!

$> greet --help

Usage:

> greet {flags} <name>

Flags:

--loud

-h, --help: Display the help message for this command

Parameters:

name <string>

Input/output types:

╭───┬───────┬────────╮

│ # │ input │ output │

├───┼───────┼────────┤

│ 0 │ any │ any │

╰───┴───────┴────────╯

Pretty cool, huh? Now let’s prepare for a debut real shell script.

As a File

The file would be like any other file. This is an example script:

#!/bin/env nu

print "Hello, world!"

This works as well:

#!/bin/env nu

def main [] {

print "Hello, world!"

}

And we can execute it like any other shell script:

$> ./script

Hello, world!

Great. Now the magic here is how we can tweak the parameters that the main function accepts. That’d be the valid arguments for our script.

I have written a quick example shell script:

#!/bin/env nu

use std repeat

def repeat_string [str: string, amount: int] {

if $amount > 0 {

$str | repeat $amount | str join

}

}

# Focus on doing something (starts a timer).

def main [--duration: duration = 30min] {

mut elapsed = 0sec

print $"(ansi blue)(ansi i)FOCUS!(ansi reset)\n"

while $elapsed < $duration {

sleep 1sec

$elapsed += 1sec

print -n "\e[1A\e[G\e[2K" # move one line up, go to first column and clear the entire row

print -n $"(ansi green)(ansi i)Time left:(ansi reset)(ansi purple) ($duration - $elapsed)(ansi reset)"

print -n "\e[1B\e[G\e[2K" # move one line down, go to first column and clear the entire row

let bar_lim = (term size).columns

print -n $"(repeat_string "=" ($elapsed * $bar_lim // $duration - 2))>"

}

print "\nTime's up!"

notify-send "Time's Up!" $"You have focused for ($duration)."

aplay ("~/.bel.wav" | path expand)

}

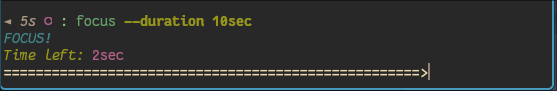

Which just starts a timer:

And of course, we get help page and documentation as well!

$> ./focus --help

Focus on doing something (starts a timer).

Usage:

> focus {flags}

Flags:

--duration <duration> (default: 30min)

-h, --help: Display the help message for this command

Input/output types:

╭───┬───────┬────────╮

│ # │ input │ output │

├───┼───────┼────────┤

│ 0 │ any │ any │

╰───┴───────┴────────╯

Crazy good and quick. I don’t think I’ll ever be in mood to write POSIX sh (or Bash) scripts anymore X)

Bonus: Do Not Try at Home

I tried doing Advent of Code using Nu Shell. Well okay, without it, I probably won’t know Nu as I know it now, but no matter what:

- It’s slow (very)

- Good luck accessing arrays like

\$array | get \$idxand re-implementing common algorithms